Confined benefits

The pension schemes propping up private prisons and why change is coming

The footage is grainy, but you can still make out the details. Thick smoke rises ominously from behind the prison’s tall, red-brick Victorian walls. Outside the gates, the usual white shirts of the prison staff give way to the black boiler suits of riot police officers. As officers form a cordon around the parameter to ensure no prisoners escape, their translucent riot shields glisten in the unnatural orange glow of the street lights. G4S, it had become clear, had lost control of HM Prison Birmingham.

This was the scene on December 16 2016. A riot, spreading across four of the 11 wings of the prison and involving up to 600 of its 1,450 inmates, successfully wrestled control from the authorities for 12 hours. Specially trained Tornado Teams, elite officers carrying sidearm batons, were backed up by 25 riot police and managed to regain control the following morning.

Less than 20 miles down the road in Wolverhampton, at the headquarters of the West Midlands Pension Fund – one of many public and private sector pension schemes backing prison operator G4S – the mood must have been less frantic. Shares in G4S were shrugging off concerns about the wider outsourcing industry and tracking higher along with the FTSE 350, the index that delivers exposure to private prisons to a huge array of investors.

But experts argue the chaos that engulfed HMP Birmingham highlighted a longer-term problem for pension scheme investors – the potential end of outsourcing – as poor conditions stir up campaigners against private prisons and their investors.

According to Andrew Neilson, director of campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform, the HMP Birmingham riot was a landmark on the road to its renationalisation. “The riot saw, for the first time in many years, police officers wearing riot gear lining up on the residential streets of a major English city,” he says. While not a trigger for renationalisation, he adds that “it was a major step on the journey towards the government accepting that G4S was unable to run the prison”.

On August 16 2018, Peter Clarke, chief inspector of prisons, sent an urgent notification to justice secretary David Gauke to retake control of the prison. He wrote: “There is an urgent and pressing need to address the squalor, violence, prevalence of drugs and looming lack of control that currently afflict HMP Birmingham.” G4S was stripped of its duties. The inspection revealed that prisoners were living in squalid and overcrowded conditions, replete with broken windows “cockroaches, ... rats and other vermin”. Mr Clarke concluded: “There can be little hope that matters will improve until there has been a thorough and independent assessment of how and why the contract between government and G4S has failed.”

Finally, in April this year, the government permanently renationalised HMP Birmingham.

A G4S spokesperson said: "HMP Birmingham is an inner-city, Victorian era remand prison which faces exceptional challenges including high levels of prisoner violence towards staff and fellow prisoners. These challenges have been evident at HMP Birmingham under both public and private management. G4S concluded that it would be in the best interests of staff and the company if management of this prison was transferred to HMPPS."

Public money in private prisons

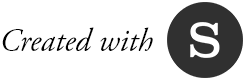

The pensions and prisons industries are more interconnected than many members might assume. Pensions Expert analysis reveals £126.3m of publicly disclosed equity investments in private security firms, held in-house by local authority pension schemes that have a private prison on their doorstep.

Before HMP Birmingham’s renationalisation there were 16 privately run institutions in the UK, sitting in the constituencies of 15 local authority pension schemes. The investigation highlighted that, as at March 31 2018, 12 pension schemes were invested directly or through managers in the shares of major prison security firms G4S, Serco or Sodexo. At least one, the WMPF with a £24.6m share in Serco, takes an active bet rather than tracking an index.

Four pension schemes held shares in the security company that operated a private prison in their very own constituency. Lothian Pension Fund, for instance, which has the Sodexo-run HMP Addiewell in its jurisdiction, held £4.58m in Sodexo shares as at March 31 2018. It says it has since sold its stake in that company. Northamptonshire Pension Fund, which has the G4S-run HMP Rye Hill in its jurisdiction, held £1.15m in G4S alongside two separate holdings in Serco totalling £5.27m.

Avon Pension Fund, which has the Serco-run HMP Ashfield in its jurisdiction, had £231,903 in Serco shares as at March 31 2019.

South Yorkshire Pensions Authority, which has the Serco-run HMP Doncaster in its jurisdiction, had investments in all three private security companies, holding £864,360 in Serco, £1.79m in G4S and £893,932 in Sodexo. It says it has since sold its stakes in all three companies.

The largest investment came from Greater Manchester Pension Fund, which has the Sodexo-run HMP Forest Bank in its jurisdiction, which held £44.5m of Serco shares and £13.9m of G4S shares.

Our investigation focused on 15 local authority pension schemes that had a privately run prison on their doorstep, but there are 89 local government pension schemes in England and Wales and 11 in Scotland. Hence total exposure to the prisons industry is likely to be much higher.

GMPF said that it was reviewing outsourcing firms carefully. A spokesperson said: “Following a spate of recent crises in the broader [outsourcing] sector, our responsible investment adviser has the sector under review. Concerns about human capital management within such business models are uppermost in our minds.”

Lothian, SYPA and Staffordshire all confirmed they had since divested from the prison industry. Surrey Council said its pension fund’s “primary duty is to invest with a view to optimising returns to meet the pension obligations of its pension members”. It added that the fund takes ESG risk seriously. The remaining schemes did not respond with a direct statement.

Governance risks to the fore

In November last year, then prisons minister Rory Stewart announced that the government would build two new prisons and open them to tender, emphasising that it remained “committed” to privatised services. But current upheaval in the political sphere, and the possibility of a Labour government led by Jeremy Corbyn, reinforces the prospect of lost contracts for outsourcers and lost returns for pension scheme investors.

On the back of a series of failings in the private sector, Labour’s shadow justice secretary, Richard Burgon, has committed to ending the tendering process for private prisons. “Labour has repeatedly warned that the Tories’ ideological obsession with running prisons for private profit is dangerously flawed,” Mr Burgon said in response to HMP Birmingham’s renationalisation in April.

Labour's motion calling on the government to end its plans to sign new private prison and probation contracts just passed in Parliament.

— Richard Burgon MP (@RichardBurgon) May 14, 2019

Privatisation has caused chaos across our justice system.

The Tories must end their privatisation obsession. pic.twitter.com/gyfKNtxVW9

“A Labour government will put an end to the scandal of our prisons being run for private profit,” he continued. This presents a potential risk to investors’ capital if share prices fall.

Rachel Haworth, UK policy manager at ShareAction, makes the case that equity investments in the private prison system are not just morally questionable, but are also increasingly bad business.

“Financially speaking, the dependence of prison providers on winning government contracts amid the threat of renationalisation also makes them risky business, not to mention the reputational risks associated with private prison scandals hitting the headlines,” she says.

“G4S is just one example of the failure of private prisons, as the security giant had a private contract for HMP Birmingham stripped this year due to appalling mismanagement.”

It’s nothing to do with politics at all, it’s to do with a perceived stream of income

Clive Betts, Labour MP and chair of the all-party parliamentary group on local authority pension schemes, agrees. He tells trustees it is their duty to consider the potential fallout from any failure and renationalisation of private prisons: “I think it’s the sort of thing that any investment adviser to funds should be taking account of.”

He adds: “Irrespective of the politics... because of the potential impact on future earnings then that should be taken account of, it’s just a matter of course as your duty as a trustee.”

There are signs this is already starting to happen. Howard Bluston, an independent adviser who currently advises the pensions committee of the London Borough of Harrow, says he advises clients not to make investments that might be subject to future political shocks. “I don’t think they should be [investing] at all. I advise my clients not to do it for the political risk,” he says.

Mr Bluston considers investments in prison operators as a clear example of a governance risk pension funds would be wise to avoid. “It’s investment performance that is paramount [with environmental, social and governance]. It’s nothing to do with politics at all, it’s to do with a perceived stream of income,” he says.

How likely is renationalisation?

The prison divestment campaign is well established in the US, where penal policy is a political battleground. President Donald Trump has expanded the remit of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement to arrest and deport illegal immigrants, proving lucrative for private prison companies.

Campaigners urging divestment from private prison companies – arguing that they are unethical and threaten detainee safety – have found success.

A slew of public pension funds have now divested, including the $227.8bn (£179.3bn) California State Teachers’ Retirement System and the $194bn City of New York Pension Fund, as well as funds in Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

In the UK however, discussion of the topic has remained limited to more financial considerations, and as such the dangers of investment hinge largely on whether a new prime minister, presumed to be Boris Johnson, would renationalise the prison sector.

Dr Amy Ludlow, senior research associate at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology, says private firms have not always been successful at delivering the incredibly complex service of prisons management.

“The promises of privatisation, as they are often politically pitched... are not necessarily lived up to in practice, or at least are much more complex in practice,” she says.

Reform, including renationalisation and other measures such as drastically reducing the size of the UK’s prison population, is gaining political traction. “I think there is a tendency to present privatisation as a catch-all solution to all of the ills of the public sector. And that is fundamentally not true,” Dr Ludlow says.

But Dr Ludlow points out that the public versus private debate is a red herring, with instances of quality and poor performance spanning both sectors. “There is no monopoly on good or bad performance related to management type,” she says.

This is corroborated by Mr Neilson, who identifies a “race to the bottom” among all prisons because of the austerity agenda of Conservative-led governments.

As it stands, Labour is committed to bringing prisons back into public hands, whereas the Conservatives still champion the private sector. Predicting the likelihood of renationalisation is just as difficult as predicting the winner of the next election.

What are funds doing about it?

With the future of prison privatisation uncertain, LGPS pooling offers schemes an opportunity to consider the long-term prudence of their shareholdings in private security firms.

The Northern LGPS pool confirmed that, to account for governance risk, it has begun engagement with outsourcing firms.

“The fact that some privatisation of prisons has hardly been successful [means] that those companies put at risk their future contracts under any government, but certainly a Labour government might take a harder view of that,” says Mr Betts.

He tells pension funds to monitor the situation closely. “That’s something the trustees of the pooled funds certainly should be looking at, in terms of both future investment and [asking] questions at annual meetings.”

While LGPS pools may have the scale to take action, private sector investors in pooled funds have a tougher time.

Research by the Association of Member Nominated Trustees this year discovered a “continued unwillingness” of fund managers to accept trustee voting direction on environmental, social and governance.

“All but the largest pension schemes are facing an almost blanket refusal by fund managers to accept their voting policies in pooled funds,” says AMNT founding co-chair Janice Turner. Given that pooled fund engagement is often a blunt instrument, more schemes may begin seriously considering divestment.

HMP Birmingham is only the most recent scandal to hit the private prison network. In May 2016, the government stripped G4S of its contract for Medway children’s prison in Rochester, Kent, after concerns over potential excessive use of force.

Public sector prisons also give rise to instances of alarming conditions, such as HMP Bristol, which entered special measures last month.

But private prisons tend to be more violent, with 156 more assaults per 1,000 prisoners in private adult prisons in England and Wales compared with their public sector counterparts.

For some, this presents a clear moral risk. Mr Neilson questions the ethics of extracting profit – by both security companies and pension schemes – from a system of human punishment.

He says: “All prisons are places of human misery. They are places where people are punished, where violence and self-harm will always be a part of the nature of the institutions, because people are being held there against their will.

“It has always seemed to the Howard League that it is immoral for shareholders to make profits off the back of people being punished.”

Ms Haworth agrees. “Investing in the private prisons system is a miserable way to make money as it necessitates the incarceration of humans to run a profit,” she says.

“We doubt whether local authority workers would want their money invested in this way.”

The law: Risk vs ethics

For Mr Betts, morality should not figure in trustees’ investment decisions. “What authorities can’t do is to pick and choose investments simply based on the politics of a situation,” he says.

UK law seems – at first glance – to side with Mr Betts. The Law Commission, in a 2014 report on ‘Fiduciary duties of investment intermediaries’, set out that “the primary concern of trustees must be to generate risk-adjusted returns”.

For Mr Betts, this is evidence that trustees must prioritise maximising profits over moral considerations. “Ultimately, they have a fiduciary duty that is primarily their responsibility,” he says.

But the Law Commission’s guidelines are more ambiguous than Mr Betts suggests. The report continues: “However, the law is flexible enough to accommodate other concerns. Trustees may take account of non-financial factors if they have a good reason to think that the scheme members share a particular view, and their decision does not risk significant financial detriment to the fund.”

The non-financial ethical considerations of scheme members can become a legitimate pretext for trustee (dis)investments.

Mr Neilson asks pension schemes to question whether their members would be happy to learn their capital is being invested in private prison firm shares. “I think that [pension funds] do need to think about these moral questions,” he says.

“Particularly because, I suspect, the teachers, nurses and police officers whose pensions are being saved, as individuals many of them would be horrified to realise that’s where their money is going, and they would want the [pension] funds to think again about what they are choosing to invest in.”

Last year, the government scrapped a proposed requirement for schemes to prepare a separate statement on member’s views. It replaced it with an optional policy on non-financial factors, including members’ ethical concerns, and social and environmental impact considerations. Whether schemes take this up remains to be seen.